This post reflects research and analysis over the past year conducted with one of the largest spec traders in voluntary carbon credit markets.

Summary

- A significant and increasing number of the world’s largest companies have net zero commitments, which require them to reduce carbon emissions and then offset remaining emissions by purchasing carbon credits. For net zero purposes, a company’s emissions include not only the carbon it emits directly, but also emissions from its energy sources and supply chain. Most global carbon emissions are “upstream Scope 3” emissions, or emissions occurring in the supply chains of final products.

- There are two possible approaches for companies to reduce their supply chain emissions, which this post refers to as the “bundled” and “unbundled” approaches. The EPA, the GHG Protocol, the WEF and others implicitly advocate the bundled approach, which requires a company to examine and incorporate the carbon attributes of each unit of physical material used to make its products. In this approach, a company can only reduce its upstream Scope 3 emissions by switching to greener suppliers or by working with existing suppliers on an individual basis to try to convince them to invest in lower-emission operations. Because this approach lacks a scalable mechanism to incentivize suppliers to participate in corporate net zero efforts, it is largely failing.

- This post argues in favor of the unbundled approach. A new approach to Scope 3 emissions, it is analogous to a system currently in use for reducing Scope 2 emissions, specifically the multibillion-dollar renewable energy certificates (“RECs”) market. In that case, energy emissions are deemed offset even though a company continues to use normal grid energy, provided it separately purchases RECs from a renewable energy generator. The raw material (grid energy) is unbundled from its carbon attributes. A company that buys and retires RECs can therefore consider it is “powered by renewable energy” even if it continues to use the standard electricity grid.

- Applying this approach to upstream Scope 3 emissions, the carbon attributes of raw materials would be unbundled from the materials themselves. A company could buy a material from whatever source is most cost effective – including in commodities spot markets – and separately purchase carbon attributes from suppliers of the material that use low-emissions production methods. Selling these carbon attributes would represent a new revenue stream for low-emission suppliers, just as sales of RECs have become a new revenue stream for renewable energy generators. This new revenue stream provides a missing incentive for suppliers to invest in emissions reduction.

- Bootstrapping an unbundled system in which carbon attributes are sold separately from base materials in a network of parallel attribute markets presents challenges. Overcoming these challenges likely requires tokenizing carbon attributes. The advantages of tokenized carbon attributes include (1) solving the “double spend” problem in offset markets, (2) leveraging token incentives for early adopters to bootstrap the network, (3) allowing directed token emissions to expand the system from its early use cases, (4) creating a scalable, permissionless network and (5) lending greater credibility to the attribute certification process.

Introduction

This post introduces the concept of unbundling raw materials with their associated carbon attributes as a new approach to reducing supply chain, or “upstream Scope 3” emissions. It argues that an unbundled system of separately traded carbon attributes would provide a missing economic incentive for suppliers to reduce their emissions. It first briefly outlines net zero initiatives, carbon credits and the different categories of carbon emissions. Second, it examines energy emissions and the renewable energy certificates (“RECs”) market. The RECs market is an example of an existing unbundled market, in which emissions are offset where a company (a) continues to use normal grid energy and (b) separately purchases RECs from a renewable energy generator. Third, it looks in greater detail at the dynamics of supply chain emissions that make this category especially difficult to mitigate. Fourth, it examines the current bundled market approach to mitigating supply chain emissions, highlighting the reasons why it is largely failing. Fifth, it describes the advantages of a system analogous to RECs for supply chain emissions. Sixth, it argues in favor of tokenizing this system of unbundled carbon attributes.

1. Net zero, emissions categories and carbon credits

Companies with net zero commitments aim to cancel out the carbon effects of their operations by reducing carbon emissions to the extent possible and then buying carbon credits representing the removal from the atmosphere of the remaining carbon their operations emit. More than a third of the world’s largest companies now have made net zero commitments. 51 countries (manly in the developed world) have net zero emissions targets, often backed by legislation binding on companies. This has led to a boom in carbon credit markets, which now exceed $100 billion in value and continue to grow. Carbon credit markets include compliance markets, in which companies buy carbon credits to meet regulatory emissions requirements, and voluntary markets, in which companies buy carbon credits to meet emissions goals they set themselves. The voluntary market is expected to reach between $10 billion and $40 billion by 2030.

There are three basic categories of emissions: the emissions resulting from a company’s direct operations (“Scope 1”), emissions from the energy source powering its operations (“Scope 2”) and emissions in its value chain (“Scope 3”), divided between supply chain emissions (“upstream Scope 3”) and emissions from customers using the company’s products (“downstream Scope 3”). The focus of this post is upstream Scope 3 emissions, or supply chain emissions, and the solution it proposes is analogous to a system currently employed with respect to Scope 2 emissions, examined in greater detail below.

Because Scope 1 emissions directly result from the company’s operations, the company often has better options for reducing them, like investing in new production methods or technologies. Scope 2 emissions are harder to mitigate because a typical business doesn’t generate the energy it uses in its operations and therefore has limited ability to change how this energy is generated. Scope 3 emissions – and in particular upstream emissions – are even harder to mitigate because they are produced by other businesses in the company’s supply chain. A company rarely controls its suppliers’ operations, and usually has limited information about how they work, so even quantifying supplier emissions can be challenging, let alone reducing them. To make matters worse, Scope 3 emissions account for a majority of global emissions and are frequently most of an individual company’s emissions.

2. RECs: the multibillion-dollar meme in Scope 2 emissions reduction

Reducing Scope 2 emissions presents a challenge for businesses, most of which don’t choose how the energy they use is produced. Rather, most businesses power their operations by simply plugging into the existing electricity grid provided by their local public utilities. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly common to see a business advertising that it’s “powered 100% by renewable energy.” In most cases, this business continues to use energy from a normal electricity grid. In addition, it separately pays a renewable energy generator, like a wind farm, for renewable energy certificates (“RECs”), which represent the “renewability” of energy produced by a generator like a wind farm. In other words, the business uses energy from the traditional, convenient source – the normal power grid – and separately buys the carbon attributes of an equivalent amount of renewable energy. A business that buys RECs equivalent to the non-renewable energy it pulls from the grid can then claim it is powered by renewable energy. In addition to this voluntary RECs market, there is also a compliance market, in which generators themselves purchase RECs if they are unable to meet a government-mandated minimum percentage of their overall production derived from renewable generation projects, known as “Renewable Portfolio Standards.”

As an alternative, it would be possible for a business to produce its own renewable energy or to plug directly into a renewable source. Imagine a “100% renewable-powered” brewery buying the parking lot next door and installing a solar array. Or imagine the brewery relocating its operations next to a wind farm and plugging into the wind generator directly. In each case, the brewery would be buying energy bundled with renewable carbon attributes. These options do exist, but for the average company they would be prohibitively complex and expensive. Separately buying RECs, on the other hand, is sufficiently cheap and easy that it is a viable option for many more businesses.

One might note that buying RECs doesn’t change the physical source of the energy powering the brewery’s machines: it still derives from whatever mix of generation methods gets aggregated in the grid, which may include a mix of renewable and non-renewable sources. Indeed, the RECs market is based on meme taking hold of energy markets that the carbon attributes of renewable energy can be unbundled and sold separately from the energy itself. It therefore doesn’t matter if a company uses some non-renewable grid energy as long as it separately pays for an equivalent amount of a renewable generator’s carbon attributes. This meme has emerged for good reason. Before the RECs market existed, much of the demand for renewable energy was hidden. A brewery might have wanted to use renewable power, but it wasn’t willing to do so at the high cost of, for example, building a solar farm or moving its operations next to a wind farm. Market demand for renewability is price elastic: if “renewability” is too expensive, demand for it evaporates.

Crucially, this dynamic can impede growth on the supply side. If a wind farm costs more than a non-renewable generator like a thermal plant to build and operate, but both pump electricity into the same grid that cost customers the same amount to use, then all else being equal there is no incentive to build a wind farm. Because selling RECs provides an additional revenue stream for wind farms, an incentive exists to build one even at a higher marginal cost. As it turns out, there was real demand for renewable energy at a reasonable price and allowing companies to use grid energy and separately pay for renewability helped unlock it. RECs were a $9.3 billion market in 2020, projected by some estimates to reach as much as $100 billion by 2030.

There is an ongoing debate about the effectiveness of RECs, with some researchers arguing that voluntary RECs programs compete with the compliance market, citing reduced sales in voluntary RECs markets where governments mandate increased renewables generation through Renewable Portfolio Standards. Others argue that RECs markets still don’t offer developers a reliable risk-adjusted revenue stream, and therefore have a negligible influence on the economic feasibility of new renewable generators. Still others decry the potential for “double spending” of RECs, where (a) renewables generators sell RECs and also count the renewable energy underlying the RECs toward Renewable Portfolio Standards or (b) companies fail to properly retire RECs and either use them twice or use them and then sell them in the secondary market. These are all valid concerns that must be addressed in any unbundled carbon attribute market.

RECs are a market-based system that serves as a tool for companies to offset Scope 2 emissions and for regulators to push electricity generators to increase their renewables production. In both cases, the key characteristic of RECs is that they incentivize generation companies to bring more renewable energy online by separating the carbon attributes of energy and creating an additional revenue stream for renewable projects – and, in the case of the compliance market, a new expense for non-renewable generators. This characteristic is important to keep in mind when examining upstream Scope 3 emissions, a category in which corporate net zero efforts are thwarted by a lack of economic incentives for supplier participation.

3. The hard problem of upstream Scope 3 emissions

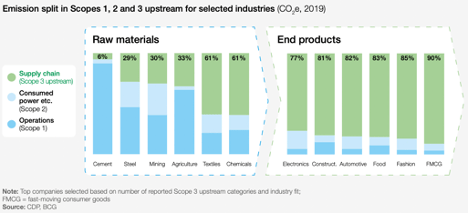

Global greenhouse gas emissions are highly concentrated in the supply chains of a few particular industries. Indeed, eight specific supply chains, including electronics, fashion, automotive and construction, account for more than 50% of all global emissions. In these industries, the vast majority of carbon emitted in making an end product are often upstream Scope 3 emissions – 85% in the case of fashion, for example.

[https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Net_Zero_Challenge_The_Supply_Chain_Opportunity_2021.pdf]

Because most carbon emissions occur in supply chains, one might assume supply chain emissions are an expensive problem to solve. These expenses can be quantified in terms of the additional cost that cancelling out emissions would add to the prices final customers pay for products. In reality, however, the added cost to final products of reducing upstream Scope 3 emissions is curiously small. The WEF estimates that if suppliers used readily available emissions-reducing technologies, the total cost of mitigating 100% of global supply chain emissions would add only 1-4% to the costs of end-consumer goods.

That modest figure begs the question: if supply chain emissions are such a big problem, and mitigating them is relatively cheap, then why isn’t this already happening?

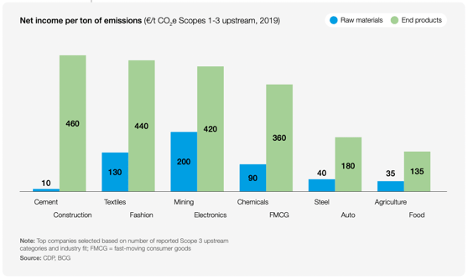

The answer is that reducing Scope 3 emissions presents a massive coordination problem among actors with different economic realities and incentives. A company making a finished consumer product would often be willing to incrementally adjust its prices or margins to mitigate supplier emissions, especially if it has a net zero commitment. But a raw materials supplier, on the other hand, does not think in terms of end-consumer costs; it understandably must focus on its own margins. And its margins are almost certainly slimmer than that of the end producer. Indeed, end producers profit significantly more from suppliers’ carbon emissions than do the suppliers themselves.

The chart below illustrates that, even in industries in which most emissions occur in supply chains, the end producer earns most of the net income generated in the value chain for which the carbon is emitted.

[https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Net_Zero_Challenge_The_Supply_Chain_Opportunity_2021.pdf]

Whereas end producers have larger margins and therefore more to spend on carbon mitigation, raw materials are typically produced with slim margins in countries that lack climate regulations, and because these materials are often sold in fiercely competitive commodities markets, even a small marginal cost increase for a supplier to reduce its emissions could render the supplier uncompetitive in the market.

The crux of the problem is that although companies with net zero pledges expend significant and increasing resources on the problem of supply chain emissions, the current approach for addressing these emissions lacks a scalable mechanism to transfer value from end producers to suppliers as an incentive for suppliers to invest in lowering their emissions. This problem is reflected in the dearth of actionable guidance on Scope 3 emissions reduction from entities like the EPA, the WEF and the GHG Protocol. For example, whereas the EPA publishes extensive, specific guidance on reducing Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, such as a comprehensive guide for purchasing green power (predominately featuring RECs), the EPA guidance on Scope 3 emissions fails to go beyond suggestions about finding greener suppliers and trying to get suppliers to voluntarily reduce their emissions. The WEF’s Scope 3 guidance largely mirrors the EPA’s, with generic advice that companies invest in data collection on supplier emissions, integrate emissions metrics into procurement standards (i.e., switching to greener suppliers where possible) and “work with suppliers to address their emissions.”

In the current system, to reduce its supply chain emissions an individual end producer must negotiate with its suppliers to try to convince them to reduce their emissions, armed with nothing more than the incentives it is individually willing to offer to each supplier. Otherwise, it must somehow find new, low-emissions suppliers and integrate them into its supply network. This dynamic helps to explain why Scope 3 emissions continue to represent most global carbon emissions even though eliminating them would cost end consumers only a small amount. To meaningfully reduce Scope 3 emissions, a scalable mechanism is needed to incentivize supplier participation.

4. The bundled approach to supply chain emissions

There are two possibilities for companies with net zero commitments to reduce upstream Scope 3 emissions. The first option is to continue with the current approach, in which end producers try to switch suppliers or to convince their current suppliers to change production methods. Implicit in the current approach is an assumption that end producers should buy commodities that are bundled with attractive (i.e., low emission) carbon attributes. The bundled approach assumes the only valid way for a company to account for its upstream Scope 3 emissions is to incorporate the specific carbon attributes of each unit of physical material input into its business.

If one were to apply the bundled approach to Scope 2 emissions, the brewery in our initial example would need to ensure the specific units of energy powering its machines were produced by a renewable source to claim it is “powered by 100% renewable energy.” To do so, it would need to build a solar array in the parking lot next door, move to a location next to a wind farm, or take some other drastic action to avoid using the standard electricity grid. RECs, on the other hand, unbundle energy from its carbon attributes, allowing the brewery to continue using grid energy and to offset its carbon effects by separately buying RECs from a renewable generator. For upstream Scope 3 emissions, the bundled approach doesn’t require relocating the company, but it does require constantly reengineering its supply chain as its needs and the supplier landscape change over time.

Also implicit in the bundled approach is that companies should pay more for raw materials that are bundled with attractive carbon attributes. But the increased costs in a bundled market are not transparent. These can include both indirect costs (including the costs of negotiating with current suppliers to change production methods, finding and switching to new suppliers, modifying supply chains, investing in complex carbon accounting systems, etc.) and direct costs (paying a higher price for materials produced by lower-emissions suppliers). In the bundled approach, it is hard to know how much a company is paying for carbon attributes, and it is even less clear to what extent these increased costs could incentivize suppliers to reduce emissions. Suppliers may only be sure a few of their customers would be willing to pay for the same material bundled with better carbon attributes, which would reasonably deter them from incurring the up-front costs of emissions reduction.

If the point of the bundled approach is to ensure that each physical unit of a business’ inputs are produced using the lowest possible emissions, it is ironic that in practice this approach pushes businesses to rely on generic carbon credits. Although generic carbon credits represent removal from the atmosphere of carbon emitted in any stage of production, including Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions, these credits are not designed to change behavior at the sources of emissions. Because carbon credits offset carbon emitted anywhere in the world, for example, they fail to solve for negative local externalities in areas with concentrations of high emission suppliers, which can become “toxic hotspots.”

Reliance on generic carbon credits also assumes projects like large-scale reforestation can originate sufficient credits in perpetuity to compensate for supplier inaction. Moreover, although generic carbon credits are today a relatively affordable option for offsetting emissions, as they increase in cost over time (as predicted by many market participants), the cost of reliance on generic credits would compromise the viability of net zero initiatives for some – perhaps many – end producers. Generic carbon credits are an ideal tool to offset emissions that truly cannot be eliminated. But when they are used to offset emissions that could be eliminated using readily available technologies and operating changes, they risk papering over solvable problems.

The bundled approach implicitly advocated by the EPA, the GHG Protocol, the WEF and others is unlikely to succeed because it fails to systematically incentivize suppliers to invest in lowering their emissions. Even in the unlikely scenario in which the bundled approach works, it would result in fragmented commodities markets in which different suppliers charge different amounts for raw materials based on the carbon attributes with which the materials are bundled. Today, global commodities markets benefit from transparency, flexibility and efficiency, for example allowing companies to rely on just-in-time deliveries of raw materials purchased in spot markets. Because spot markets work like energy grids – they are pools of physically-indistinguishable, fungible commodities in which it is often impossible to know the specific production method of a particular unit – widespread bundling of carbon attributes with raw materials could render spot markets largely unworkable. Taken to its logical conclusion, even if it were possible to implement a bundled system at scale, this approach would compromise the efficiency of global commodities markets.

5. The unbundled approach to supply chain emissions

There is a second possibility. The second approach is to learn from RECs and unbundle base commodities from their carbon attributes, with commodities suppliers selling carbon attributes in a separate market. The fundamental claim here is that the same concept driving the RECs market should apply to supply chains in general. That is, it doesn’t matter if a company uses higher-emissions or spot market materials, provided the company separately pays for a low-emission producer’s carbon attributes. Unbundling base commodities from carbon attributes has the following advantages over the bundled approach:

- Unbundled carbon attributes would provide a new revenue stream for suppliers. Because a raw materials supplier with low emissions would have a new revenue stream – separately selling the carbon attributes associated with those materials – this method would provide a missing incentive needed to push suppliers to switch to lower-emissions production methods. In the bundled approach, suppliers lack an incentive to invest in operational changes apart from any eventual sweeteners offered on a piecemeal basis in negotiations with individual buyers.

- Unbundled carbon attributes would be more efficient for buyers. In the current bundled market model, end producers must individually find greener suppliers, try to convince current suppliers to reduce their emissions, and then rebuild their supply chains – many of which are already under stress. These initiatives expend significant company resources and often fail to meaningfully impact Scope 3 emissions. An unbundled market would be better for end producers: they would simply buy raw materials from the most convenient source available, including in long-term supply agreements and in the spot market, and buy carbon attributes separately in low-cost transactions.

- Unbundled carbon attributes would provide price transparency. One of the challenges in the bundled approach is that although suppliers may know of a few current buyers willing to pay more for materials bundled with attractive carbon attributes, the aggregate carbon premium of these sales can be hard to calculate and may not be large enough to pay back investments in emissions reduction. An unbundled approach adds price transparency: everyone in the market would see trading volumes and prices at which carbon attributes clear. This is important for sellers, as it would allow them to model the risk-adjusted returns in switching production methods. It is also better for buyers, which would immediately know how much the attributes cost without the need to survey multiple suppliers or engage in individual negotiations.

- Unbundled carbon attributes would facilitate emissions reduction financing. Suppliers typically finance investments like those required to change to lower-emissions production methods. An unbundled, transparent market for carbon attributes would allow financial partners to easily model the risk-adjusted returns of specific suppliers’ emissions reduction investments. In a bundled market, many – if not most – deals will continue to occur in private negotiations opaque to the broader market, and it is generally difficult to apportion the value in a given deal between the base commodity, the indirect costs inherent in piecemeal negotiations, and the carbon attributes themselves. In a bundled market, financiers considering funding emissions reductions investments would need to access private market data on bundled transactions and then attempt to manually unbundle them to understand the marginal revenue increase associated with the carbon attributes.

- Unbundled carbon attributes would reduce reliance on generic carbon credits. Because most companies pursuing net zero cannot effectively reduce their supply chain emissions in the bundled approach, they are left to offset upstream Scope 3 emissions by buying generic carbon credits. In contrast, an unbundled market of separately traded carbon attributes would target the root cause of emissions, providing concrete incentives for suppliers to change production methods. Generic carbon credits would be preserved for offsetting those emissions that truly cannot be eliminated using readily available technologies and operating changes.

- Unbundled carbon attributes would work in both compliance and voluntary markets. Like RECs, which are traded in both compliance and voluntary markets, unbundled carbon attributes would allow companies with net zero commitments to achieve their targets more effectively and would also provide a new lever for governments to mandate Scope 3 emissions reduction. A government of a country with high-emission suppliers may wish to push its producers to reduce emissions without forcing these suppliers to incur all the associated costs at once. In an unbundled market, the government could require suppliers to buy carbon attributes in the market similarly to how energy suppliers buy RECs in the compliance markets to meet Renewable Portfolio Standards. These standards could increase incrementally over time to help preserve the initial competitiveness of a local industry without ignoring its emissions problems.

6. Tokenization of carbon attributes

No unbundled system currently exists in which carbon attributes are sold separately from base materials. Bootstrapping a network of parallel carbon attribute markets presents challenges, and overcoming these challenges likely requires tokenizing carbon attributes. The advantages of a tokenized system of unbundled carbon attributes include those set forth below.

- Tokenization helps solve the “double spend” problem. Carbon offsets like generic carbon credits and RECs can only be used once. Companies must retire offsets as they are used. This retirement process is currently manual, which raises the possibility that a company might use offsets twice or sell in the secondary market offsets it has already used. Tokenized systems are designed to prevent double spending by registering each unit on a blockchain that is transparent to the public, a characteristic that has led many to advocate for blockchain solutions to carbon credit custody and tracking. In an unbundled attribute system, retired tokens would be “burned” and therefore unavailable to sell or use again. In addition, members of the public would be able to see the volume of carbon attributes purchased and retired by any market participant. For public companies, the volume of purchased and retired attributes could be compared to the volume of the raw material used by the company in a given period, which can often be extrapolated from the financial and operating information the company already reports publicly.

- Tokenization helps solve the “cold start” problem. Even transparent, unbundled markets would confront a “cold start” problem. Although the existence of an unbundled market for carbon attributes would allow sellers to model the potential revenue upside of changing their production methods, the initial volumes traded on such markets would be negligible. The unbundled approach therefore still requires coordinating initial action among a dispersed network of buyers and sellers to kickstart this market. Tokenized systems can help tremendously to solve cold start problems by offering outsized rewards to first movers in the form of token emissions. One example of this is Helium, the decentralized network of signal-emitting hardware. Helium managed to kickstart a network now composed of nearly a million LORAWAN hotspots by offering token rewards to hotspot providers, many of whom entered the network before it was generating revenue. Helium is now leveraging its market position to create a decentralized cellular 5G network. These cases exemplify the power of token rewards to incentivize early adopters by allowing them to own a outsized piece of the network if they begin using it before it has enough density to generate meaningful revenue.

- Tokenization allows using directed token emissions to expand from early use cases. In addition to solving the cold start problem, tokenized systems would help carbon attribute markets expand from early use cases into a larger network of markets. Because each specific physical material must be paired with carbon attributes from producing that material, the unbundled approach requires a network of standardized but separate markets running in parallel. For example, a clothing manufacturer would need to pair cotton purchases with tokens representing low-emissions cotton, and an EV battery manufacturer would need to pair nickel purchases with tokens representing low-emissions nickel. The best early markets for carbon attributes will likely be (a) markets that are concentrated among smaller groups of both buyers and sellers and (b) markets in which a large proportion of buyers already have net zero commitments. Initially, the unbundled system would proactively seek out the best use cases, create markets for them and direct token emissions to incentivize sellers and buyers to participate in those markets.

- A tokenized, permissionless network can scale quickly and efficiently. An unbundled system would ideally exist on a standardized protocol encompassing a large portion of all carbon attributes traded. While the system can direct token emissions to incentivize certain initial attribute markets, it would remain a permissionless protocol. This means that any set of market participants could create a new attribute market on a permissionless basis. At scale, the protocol would represent a one stop shop for an end producer to purchase carbon attributes to pair with all its physical inputs. Over time, one could imagine this permissionless protocol even expanding beyond carbon attributes to allow trading of other intangible attributes, for example methane performance certificates and water restoration certificates.

- Tokenization creates a more credible validation system at low cost. An unbundled system would require third-party certification or validation that the carbon attributes offered for sale are as advertised. Doing so with credibility requires third-party certification, just as generic carbon credits are certified by organizations like Verra. Validators must be compensated for their work and could be paid at least partially in directed token emissions, increasing the system’s overall capital efficiency. In addition, to increase confidence in the system, validators would be required to stake the native token to certify attributes, at the risk of forfeiting staked tokens (or “slashing”) if they commit errors or fraud. Staking and slashing are well-understoodmechanisms in cryptographic security models that would increase the overall reliability of an unbundled, tokenized system.

Tokenized carbon attributes are worthy of experimentation

Today, most global carbon emissions are upstream Scope 3 emissions, and companies with net zero commitments have poor options to reduce them. Because the current approach requires a company to bundle the specific carbon attributes of each unit of physical material it uses, the only options available are to convince suppliers to voluntarily switch to lower emissions operations, or to find greener suppliers. Crucially, this system lacks a scalable mechanism incentivizing suppliers to participate in emission reduction efforts. Unbundling materials from their carbon attributes would allow companies with net zero commitments to buy attractive carbon attributes directly from low emission suppliers, creating a new revenue stream for these suppliers and a new incentive to change production methods. There are obvious challenges to bootstrapping a new market, and tokenization would help to overcome them.

Not every Scope 3 emissions reduction initiative must necessarily involve end producers. Indeed, governments can mandate changes to production methods or incentivize them through subsidized “green” financing. These are worthwhile efforts and should continue to be pursued in parallel. But in corporate net zero initiatives, end producers take responsibility for the carbon emitted in making their products. Since most of the profits in a typical value chain accrue to the end producer, and since the cost of mitigating supply chain emissions is quite low in end-product terms, end producers are in an ideal position to act. Their efforts, however, are thwarted because no mechanism currently exists for them to do so effectively. An unbundled system of separately traded carbon attributes would provide this mechanism.

Leave a comment